The Bayeux Tapestry

We have previously looked at the history of textile art and how it’s always been crucial to how we view both the world and ourselves. Now we’re going to focus specifically on the textiles of the medieval period - how they helped tell stories to a largely illiterate population and how they were used to denote social status, as well as the techniques and materials involved in bringing these exquisite pieces to life.

One of the earliest - and perhaps most famous - examples of textile art is the Bayeux Tapestry. The word “tapestry” is somewhat misleading as it’s actually a rather epic piece of embroidery. It’s believed to have been commissioned by Odo, the Bishop of Bayeux and half brother of William the Conqueror, to commemorate William’s successful invasion of England in 1066, although other contenders include the widow of Edward the Confessor, Queen Edith, and even William himself. Most historians believe that Odo is the most likely patron, however, due to his prominent position in the events depicted on the tapestry (compared to his role in reality).

Section of the Bayeux tapestry

Somewhat ironically, the “tapestry” wasn’t made in Bayeux or even in France; it was actually made in England by English embroiderers! There are parallels with Anglo Saxon illuminated manuscripts, including designs that have been found in a monastery in Canterbury - leading some to speculate that the Bayeux Tapestry was created within Canterbury specifically. It was made from nine linen panels embroidered with crewel, or wool yarn, and is incredibly over 200 feet long. Two different types of stitching were used - stem stitching for lettering and the outlines of figures, and couching to fill in the figures. Traditionally, the stitching was attributed to the wife of William the Conqueror, Queen Matilda, and her ladies. However, it’s more likely that the work would have been carried out by nuns. It’s amazing to consider the amount of skill and effort that went into creating a piece like this.

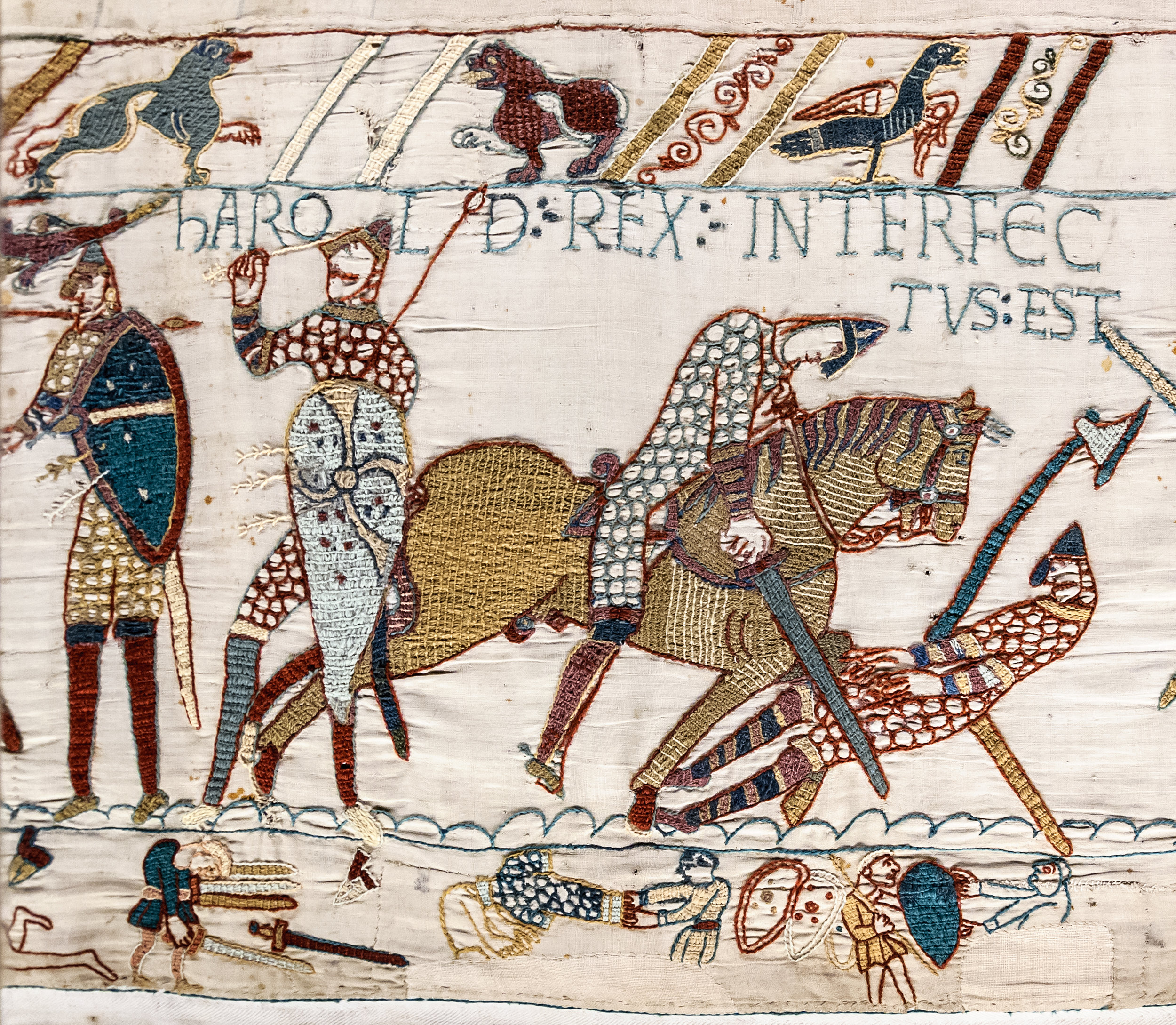

Despite showing a victorious William defeating his Saxon opponent and claiming the English crown for himself, it’s argued that the Bayeux Tapestry isn’t a straightforward piece of propaganda designed simply to celebrate the might of Normandy. The respectful depiction of Harold, including using his title of “king” and scenes that show his bravery in battle, the use of the lesser word “dux” or “duke” to describe William, and the emphasis placed on the oath that Harold allegedly swore to William (that the English throne would pass to William on Edward the Confessor’s death) have led some to believe that the “tapestry” is used as justification for the Battle of Hastings; a defence for Norman actions rather than a boast. Something that might have been aimed at easing political tensions following the Norman occupation of England. The “cartoon strip” format means that it would have been easy for people to “read”. There’s a great quote by George Wingfield Digby in his book Technique and Production: “It was designed to tell a story to a largely illiterate public; it is like a strip cartoon, racy, emphatic, colourful, with a good deal of blood and thunder and some ribaldry”.

The death of King Harold

The Bayeux Tapestry is not only fascinating and unique for the reasons mentioned above; it’s also one of the few remaining pieces of medieval secular embroidery. Much of what we know about medieval embroidery comes from religious works, particularly the form of English embroidery known as opus anglicanum. Although used for both domestic and religious purposes, most of what survives comes from within the Church, such as the copes and chasubles worn by priests. To help understand just how highly prized opus anglicanum was, a 2013 article by Dan Jones for The Spectator claims that commissioning a truly splendid piece of English embroidery during this time would probably have cost as much as a fresco by Giotto. The medieval Church would certainly have had sufficient riches to request only the very best for its clergy.

Just why was English embroidery so highly prized during this period? Firstly, the materials used were of the best quality - gold, silver and silk thread being especially common. Gold and silver were typically used to create details like halos or robes, as well as reinforcing the piece and helping it to move (the metal threads acting in a similar way to a hinge). Secondly, the level of detail involved was incredible. Silk thread was worked in (often tiny) split stitch to create movement and shading, and artistic techniques were used to create the impression of detailed features - a turn to conjure the tip of a nose or arched stitches across a forehead. There is even an example of a chasuble showing angelic wings where the stitches follow the same direction as veins on real feathers.

Contrasting with embroidery - which was typically carried out using linen with fine silk or cotton thread - the tapestries of the medieval period were generally created with wool on a loom. A tapestry is essentially a grid made with vertical threads known as warps, and horizontal threads known as wefts. The warp threads form the backbone of the tapestry with the coloured weft threads woven across the top and then pushed or “tamped” down to hide them, so all you see is an image made up of horizontal threads. Blocks of colour were used to build up patterns. Weavers often followed a design, known as a “cartoon”, that was either temporarily attached to the loom or hung on a wall where the weavers could copy it. Some of the most famous examples of tapestry cartoons are the Raphael Cartoons, now in the V&A, that were commissioned by Pope Leo X and designed by the artist Raphael.

Raphael cartoon: The Lame Man

Typically found in wealthy households, tapestries performed a dual function of decoration and insulation. Perhaps some of the best known medieval tapestries are the Devonshire Hunting Tapestries, created during the 15th century and eventually ending up in the possession of the Countess of Shrewsbury at Hardwick Hall. These magnificent tapestries were probably created in Arras, northern France; an area that was famed for its tapestry production. Arras tapestries have been described as being essentially line drawings without any of the diagonal, irregular or floating threads found in embroidery. The town prospered thanks to the patronage of the Dukes of Burgundy who were keen to increase their tapestry collections and, as such, enhance their status. However, political conflict led to a decline in Arras’ fortunes and other towns, like Tournai, stepped in to fill the void.

Tapestry weaving in Flanders boomed so much during the medieval period that a law was eventually passed regulating production. Like all bubbles, however, this one burst once the 16th century arrived due to a combination of war within Flanders and the rise of Italian Renaissance painting. Weaving took a backseat to painting but that wasn’t the end of the story. Flemish weavers, forced to become refugees, moved throughout Europe and retained the support of the rich and powerful who still required tapestries to decorate their great houses. In fact, the tradition of tapestry weaving is one that has continued in both France and Belgium well into the 20th century, despite being a technique that is centuries old. Or perhaps that’s why weaving still thrives: why change what works so well?

By Lucy Pinkstone